Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, long chastised by media and politicians from opposing parties for not seeming to have much in the way of policy, delivered a staggering amount of policy last week. Amongst Trudeau’s announcements was his intention, if his party forms the next government, to do away with the current electoral system of First Past the Post (FPTP). What it will be replaced by will be the determination of an all-party panel, but whether it’s ranked ballots, proportional representation, or something as yet unthought-of, many Canadians agree that change is good.

But while considering change, there’s still the small matter of the Canadian senate. Trudeau’s policy brief included a proviso for creating a committee to oversee Senate nominations, thus, hopefully, avoiding any future senatorial selections that seem like party payback for raising money or doing political favours. NDP leader Thomas Mulcair meanwhile has been emphatic, the Senate has got to go, and it’s not like it does any work anyway. I’m sure some senators would beg to differ in that appraisal, and even Mulcair’s own supporters, at least those who wanted Bill C-51 defeated, saw value enough in the senate to try and petition senators to use their constitutional power to stop its passage into law.

But while we consider electoral reform, and senate reform, I propose a simple question in regards to the process: why not both?

First of all, let’s dismiss the idea of abolition in regards to the senate. Pragmatically, is it worth cracking open the Constitution to stick to a bunch of political plutocrats? And at the same time, what is the likelihood that all 10 provinces are going to go in for abolition when the present Premier of Quebec, home to more than half of the NDP caucus, has said that he won’t give the end of the senate his approval. And why would he? Quebec owns one-quarter of the senate itself.

So the senate isn’t going away without tremendous effort and what maybe the greatest expenditure of political will since Meech Lake (and we all know how that turned out). Reform, however, is more easy to obtain. All it requires is a majority of the population and two-thirds of the provinces. But what form should reform take, aside from the need for a mechanism to remove senators as last week’s allegations against Sen. Don Meredith reminded us?

Putting that aside for a minute, let’s consider electoral reform, at least as outlined by Trudeau in last week’s announcement. Ranked ballots are fairly self-explanatory, but MMP, or Mixed-Member Proportional representation, is a bit trickier. In MMP, a group of seats is set aside to be filled based on party share of the popular vote. So in a vote using MMP you would vote for your local candidate, like you do now, but there would be a second column on the ballot to vote for your preferred party. Using the upcoming election here in Guelph as an example, using MMP, you could theoretically vote for Conservative Gloria Kovach for your Member of Parliament, but vote in favour of the NDP to form the government.

In 2011, the Conservatives won 166 seats and 39.6 per cent of the vote. In other words, they had 54 per cent of the seats, even though their total share of the popular vote was less than 40. Meanwhile, the Bloc Quebecois won 6 per cent of the popular vote, but won just 4 seats, which is just 1 per cent of the number of seats in the House. Now, using the New Zealand model of MMP, let’s say Canada has 300 total seats, with 220 elected MPs and 80 representing “party votes.” The Bloc wins their four seats, but under MMP they’re entitled to 14 more to be drawn from 80 seats set aside for “party votes.”

The Conservatives meanwhile, if they had won 54 per cent of 300 House, would have 162 elected MPs, but the rules of MMP mean that the Tories should tap out at 117 of the total 300 seats. In the parlance of MMP, those 45 seats are “overhang seats,” in which case, Canada’s 41st Parliament would have been made up of 345 seats so that proportionality could be better represented.

In practice this all might make more sense, especially when you’re not going off of votes cast in a FPTP election where there’s a great deal of strategic voting going on, not to mention about 40 per cent of the electorate who feels their vote “doesn’t count.” Still, in trying to explain it in its simplest terms, it’s easy to understand why MMP has failed in four different provincial referendums in the last 10 years, including one here in Ontario in 2007.

There are problems with the MMP system that should be addressed, and Trudeau himself pointed them out when he came to the University of Guelph while running for Liberal leader. For instance, who do the MPs representing “party votes” represent? Who are their constituents? Are they eligible to sit as cabinet ministers? Second, and perhaps more importantly, who chooses the people that go on the lists? Are we looking at another potential future senate-esque scandal where partisan appointments lead to accusations of runaway expenses and other betrayals of the public trust?

So here’s a radical proposal: let’s make the senate a crucible for testing MMP. Senators have to be appointed, so let’s take who gets to be a senator out of the hands of the Prime Minister’s Office and spread the right (and the responsibility) to the voters, whose share of the popular vote will determine how many senators of each party per province will get, and the people in the parties themselves, to make responsible and informed recommendations as to who gets to serve in the senate.

What would this look like? First, a quick senate tutorial. There are 105 seats in the Canadian senate with 6 each for British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Newfoundland; 24 each for Ontario and Quebec, 10 each for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick; 4 for Prince Edward Island, and one apiece for the three territories. According to the current standings there are 48 Conservatives, 29 independent formally-Liberal senators, another 7 independents and 21 vacancies. Prime Minister Stephen Harper has been understandably gun shy about more senate appointments in the wake of the near consistent drone of bad news coming out of the Red Chamber….

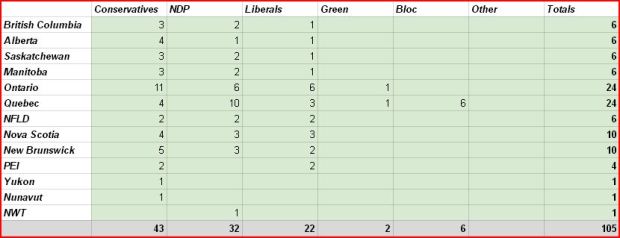

Now let’s look at what the senate would be like after the 2011 election if proportional representation had been used to choose senators. The below graph was built out of using the current allotment of senates per province, and then dividing how those senate seats are awarded through share of the popular vote in that province.

For reference, here’s the percentage of popular vote as broken down by province, from which the numbers to divide this proposed representational senate was drawn.

And this is the breakdown of House of Commons seats after Election Night 2011.

So does this solve our senate problem? Probably not 100 per cent, but a couple of things. First of all, some mechanism would have to be implemented to decide how seats are turned over. For example, if in the 2015 election, the Conservatives number of senate seats were reduced to 40 from 43, a way would have to be figured out to decide how those three seats should be given up. If they were a seat each from B.C., Alberta, and Ontario for example, perhaps the longest serving senator representing those three regions should step down. Ageist? Possibly, but part of the problem with the senate is its “job for life” status. A comfortable senate salary and its even more comfortable pension have been strong incentives for people looking for payback for favours done on behalf of the party – ask Mike Duffy – so perhaps the possibility of an early exit will dissuade some partisans from looking for their golden parachute in the senate.

Assigning seats proportionally based on popular vote in the province to whom those seat belongs may help solve another problem with the senate brought to light by the exploits of Duffy and co-defendants Pamela Wallin and Patrick Brazeau, residency. If I’m a Saskatchewaner, and I vote Conservative for a senate representative, I would be darn mad if a life-long resident of Toronto was chosen to represent me, especially if the NDP and Liberal senators were chosen from Regina, or Saskatoon, or someplace in between.

Is this system perfect? Objectively, no. For example, look at British Columbia, where the Green Party got 7.7 per cent of the vote, but that didn’t result in a single senate seat in B.C. per my system. Meanwhile in Ontario, the Greens got 3.8 per cent and did achieve one senate seat. That has to do with the number of senators Ontario has as compared to B.C. When you only have six seats, the percentage of the vote you need has to be higher than if there are 24. This could be addressed in a couple of ways, either the Greens need to achieve a better share of the vote in each province, or senate seats need to be redistributed.

Redistribution though may be another one of those tricky conversations, but one that falls within the purview in the discussion of reform. In British Columbia, each senate is supposed to represent with 775,000 people, while in Newfoundland, which has the same number of senators, each one represents 85,595. Even Ontario, which has 24 senators, has representation wildly disproportional with each senator representing 565,988 people. If we intend to keep the senate then there should be a way to reconsider who gets how many seats in much the same way we re-draw riding lines when population changes. There’s also the suggestion that the senate could add seats, but admittedly that may be a tough sell at the moment given the indiscretions of its current members.

The problem is not the senate itself. The idea of “sober second thought” is valid, and in hyper-partisan times, it perhaps makes sense to have a body that can act legislatively and not have to worry about the impact on their individual election. It’s worth noting that months before the Supreme Court ruled on the legality of assisted death, two senators, including Nancy “Cold Camembert and Broken Crackers” Ruth, pushed for legislation to make doctor assisted death legal. The senate also recently passed nine recommendations to administer the use of neonicotinoids, widely suspected to be one of the causes of collapsing beehives. It also recently pushed for more oversight of Canada’s border security agencies. Hardly the do-nothings that Mulcair’s making them out to be, and hardly the stuff that’s preoccupying the people’s house on the eve of an election either.

As for the entitlement of the senate, that may reach back to its origins and its British equivalent the House of Lords, an antiquated delineation of the so-called “elite” from the hoi polloi. Those kinds of distinctions the people won’t stand for anymore because it implies that some people are supposedly better by heredity, wealth, or status. It’s the privilege that everyone’s mad at the senate about, the nearly $1 million in over-expensed expenses. Find any two average Canadians who can explain what the senate does and it would be surprising to get even a half-correct answer, but using our party system to cultivate an apolitical body given second consideration to new laws and exploring the issues that Parliament doesn’t want to touch? What’s wrong with that?

You may remain of the opinion that the senate is at its end, and that as an institution it has run its course in relevance to Canadian society, and that’s okay. It’s a perfectly valid opinion. But let’s consider the idea that taking up the expense and effort to throw something away without at least trying to fix it first. We don’t need a senate that’s a classist holdover, and we don’t need a senate that’s a partisan retirement home, but perhaps it is prudent to create someplace that can be realized as a true body of sober second thought. In an era where government sometimes reacts without a first thought, a more reflective body should be something worth having. But only if we want it.